H͢A͢A͢R͢D͢E͢R͢

Machined imperfection feat. Eva Dixon

The interesting art is outsider art, the interesting artists are outsiders.

The big name international makers who grab me are the freaks ~ Imworth, Holzinger, Nadya ~ and people you would barely call artists… working in spaces that never get graced with gallery, whose visitors blah blah blah you read ULTRA you get the picture.

My family were truckers… I have thirteen cousins and all of them are [labourers] says Dixon.

Oh the little edit there? Though now based in London, Dixon still uses the Aussie term, tradie. Eva Dixon, who very first cameo’d in ULTRA courtesy of Charlie Henzi, is an artist who defiantly and resolutely creates outsider paintings with materials that John Ruskin would fucking hate… contained sculptural scramjets that add movement and potential to a medium that’s usually static.

This conversation takes place a little before a major new show where she will attempt to build something outlandish. So let’s see: consider this one of two.

𝑯𝑨𝑹𝑫𝑾𝑨𝑹𝑬

Dixon’s study of cultures of industry is a hands-dirty exploration of function over form.

Growing up in the Hunter Valley, my family assumed I’d pick up a trade, or [because I loved art] be an art teacher or something. Which made me wonder. What would it look like make art as a tradie?

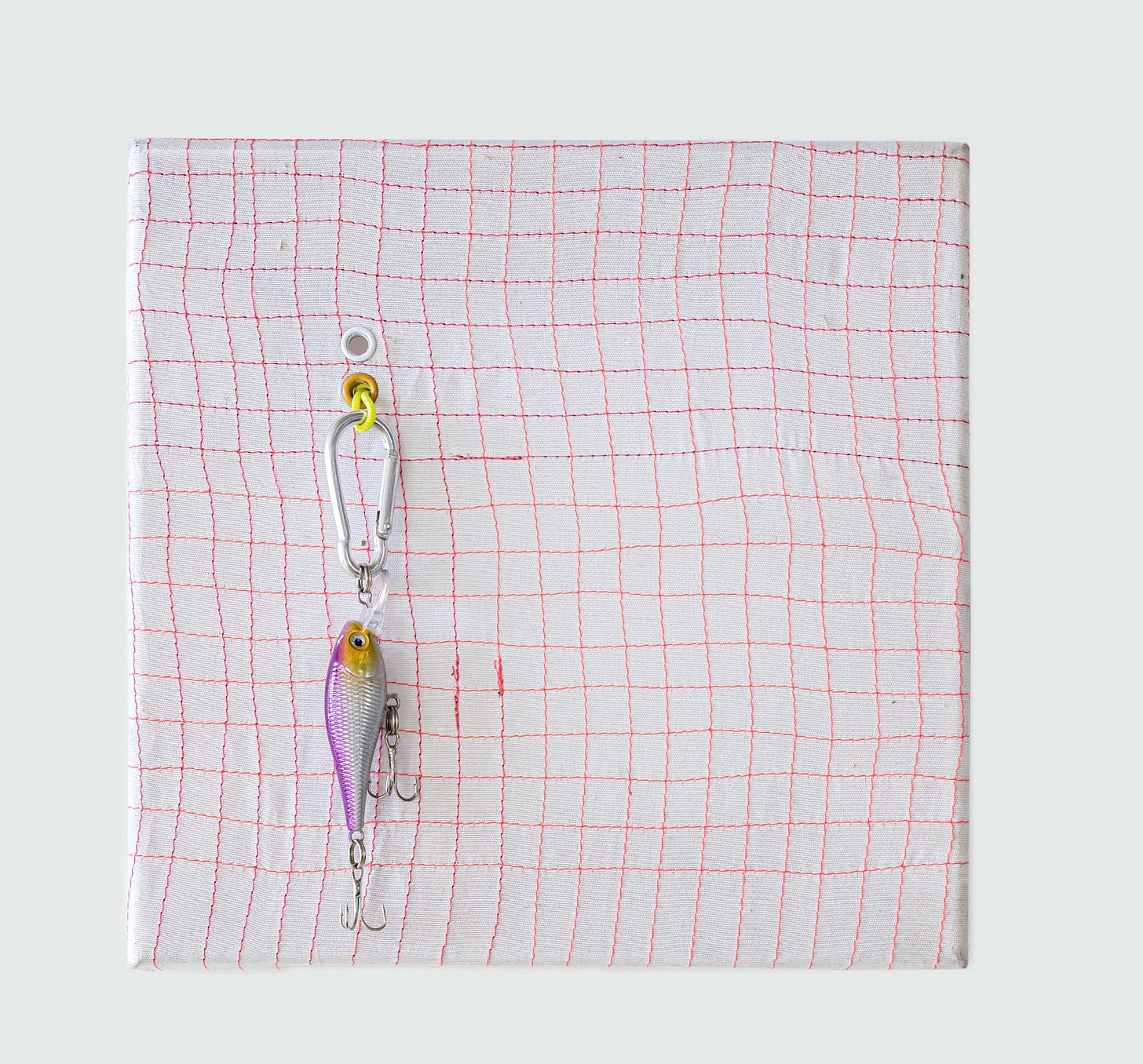

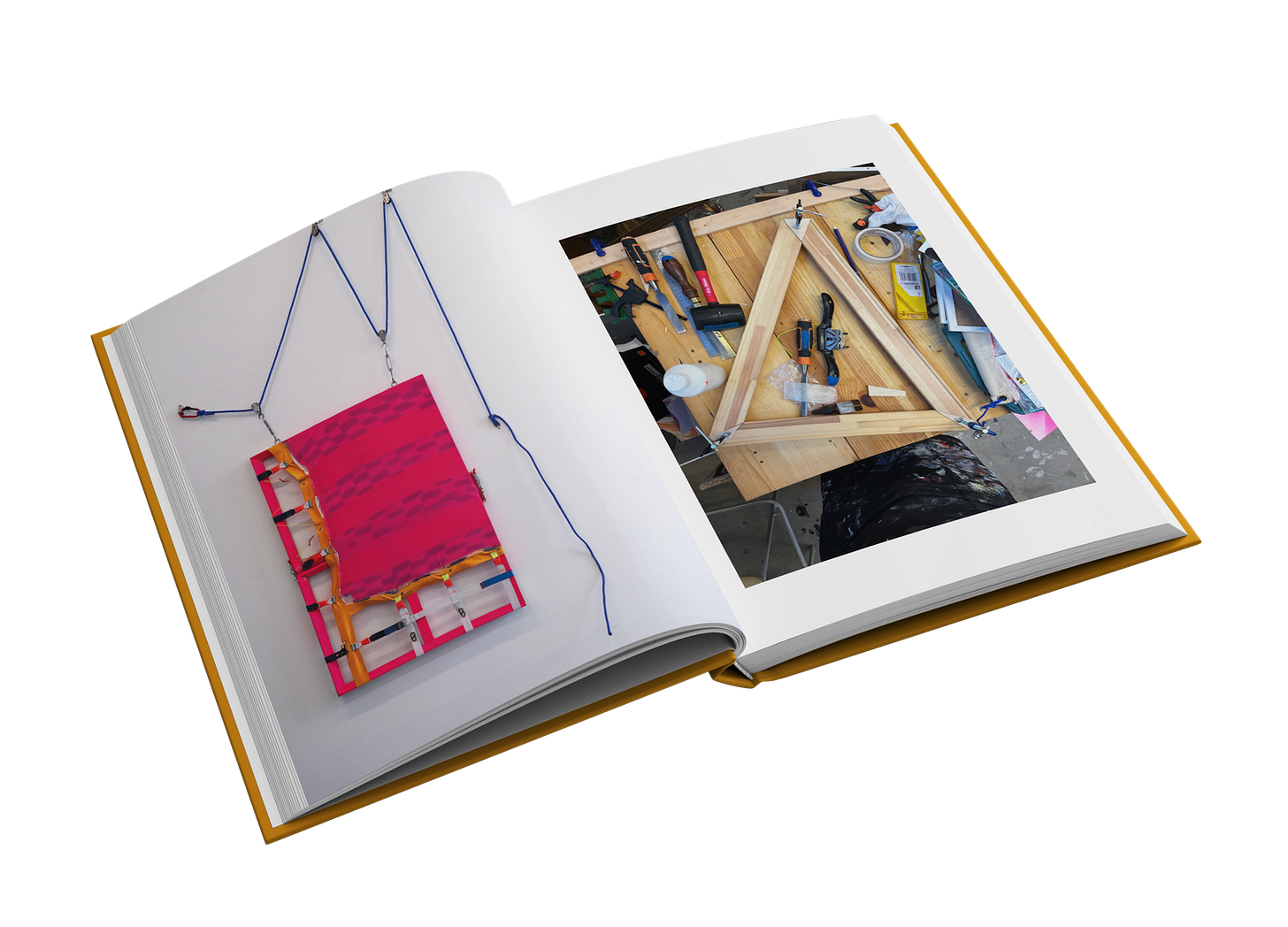

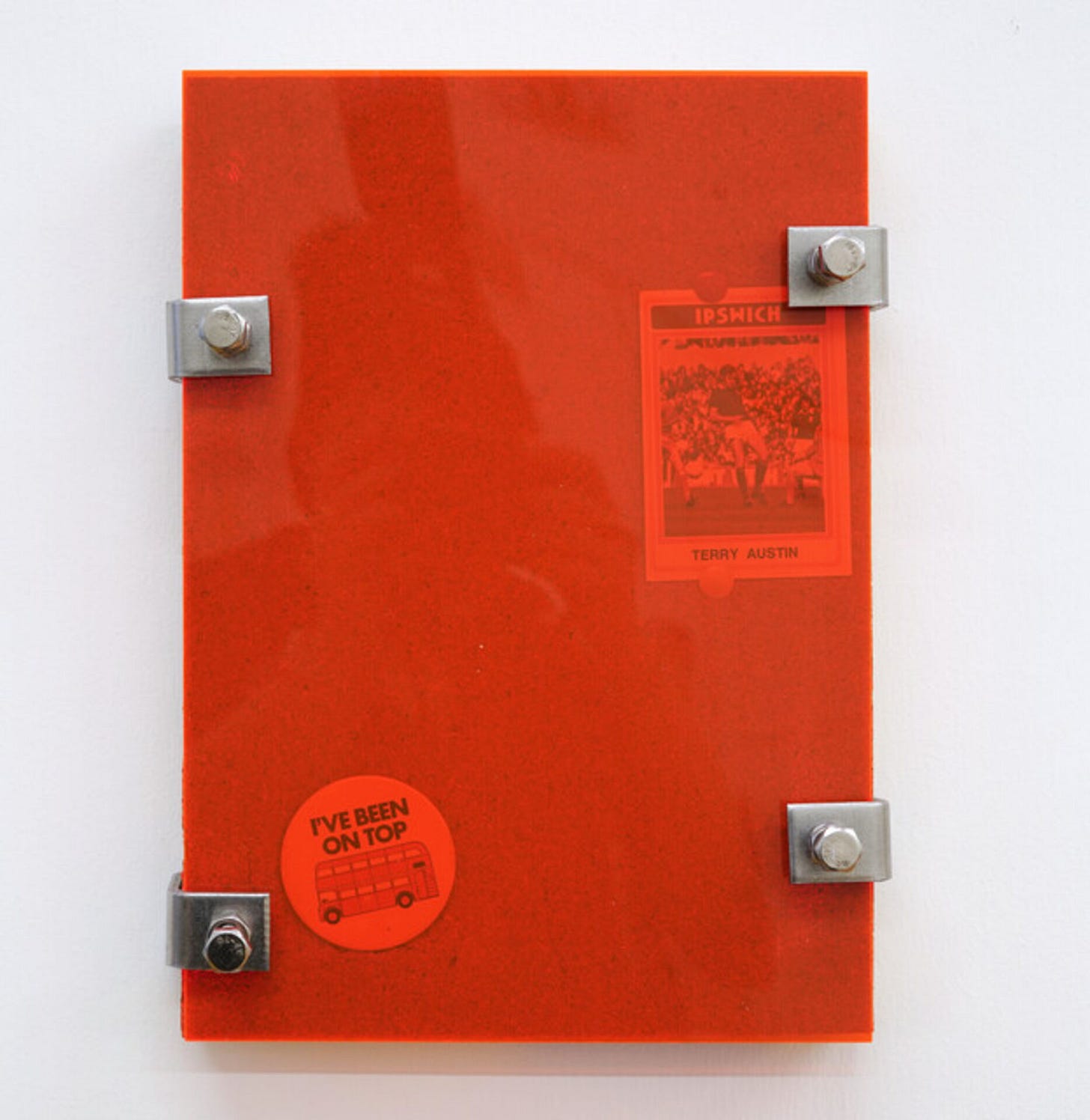

Canvas and metal collide. Pins and buckles and ratchets and vinyl, plastics, fabrics woven, metals smashed, scraped, bent, twisted, perspex pressed down with stickers and stamps and other reliquaries of small town pop culture — bringing an art thing into existence out of totally improper materials.

Three (2024) is a high vis piece of protection melded with BMX references.

Atlas (2025) is a reimagined sail, seam-taped, waterproofed and sealed.

The pieces are sprung energy; physical and felt.

Her days away from the paintings, working a series of jobs, desperate to get back to the studio, her subconscious keeps pulling in the raw ingredients on a vibes-basis… pins, cables, firehoses… an Electrolux vacuum that has a quality.

This infuses the work with controlled chaos. These paintings are a collision of kinetic materials forced into being, manipulated to their tension point right at the limit of tensile strength, the point before the snap, or the explosion.

There is a delicacy to fine art that is defied. The pieces feel set to blow.

𝑯𝑨𝑹𝑫𝑾𝑰𝑹𝑬𝑫

Too well-fabricated and it becomes dehumanised.

To make work this way is intentionally challenging.

I remember being taught — just because you’re thinking it, doesn’t mean the viewer can see it.

The process is all up there to be seen, to be felt.

I think about my conversation with Mikey Ting, about the endless precision and upskilling required to fabricate endless new objects, corralling the knowledge and materials, the methods often esoteric and highly gatekept. Forced experimentation compels creative solutions. Dixon talks to a process that is procedural but open-minded. An unfolding.

I don’t do it to get something finished. I do it for the passion, the act of learning. I do it because it’s difficult. The pleasure comes from the hardness of it - recognising that, and staying with it. To do the hard thing that almost overcomes your capacity, to deny the easy thing ~ that is truly satisfying.

So what really matters more, process or artefact?

I see a lot of first-year art students who are obsessed with outcomes. For me, that’s usually a red flag that they lack rigour. To be and sit with the process… the work is just evidence of the fact I was there.

I was thinking about Richie Culver, who’ll often talk about the struggles chipping away at an art world that’s ill-built for the working class. His take was somewhat inverse — ‘Stop trying so hard’.

As an ADHD person, this practice gives me the rare and unique opportunity to spend time in my brain. I get to walk around in it for hours, to wrestle with the work in a way that eludes me in other spaces. I get the pure satisfaction of something I can’t verbalise.

It is the doing of hard things that makes it purposeful, and this purpose is an organisation of thought crystallised through maximum effort.

There’s a commoditisation to the fine art industry, an identikit badging, profiling, discourse, a production-line element to powering out the hits.

To sit with the hardness, dwell in it, love it ~ some would find that ruinous, they’re simply not wired that way.

But to do something you love and not give it your all is criminal.

𝑯𝑨𝑹𝑫𝑵𝑬𝑺𝑺

Dixon has been outspoken about a few things, not least the challenges of having that outsider status, of resolute self-recognition as a painter however non-traditional her expression, of her work being called ‘feminine’ whenever she dares include a bit of weaving.

And yes, much of the focus of this conversation is hardness, but nestled within that is also the fluidity that is necessary to avoid calcifying, becoming brittle; of finding the softness that allows truly experimental practice.

In other words, what does it mean to meet resistance without letting it radicalise you?

It’s easy to be sensitive. But not everyone’s opinions count. And I think about how my Mum describes my work, that “I concoct things”. That in itself can be radical.

For a little while, it’s evident how Dixon has been exploring with the idea of bringing together true events to create artefacts of non-existent events.

Remember the new era of photographers, creating impossible images? Dixon’s inquiry is bringing the imagined into physicality on a new scale, starting with an exploration of NASA’s Mercury 13 - the buried story of women who never went to space, told as if they did.

There’s incredible freedom in a non-event.

The great paintings aren’t just painted. The truest events weren’t necessarily real.

If that’s challenging to grasp, the hardness is the point.

.

.

.